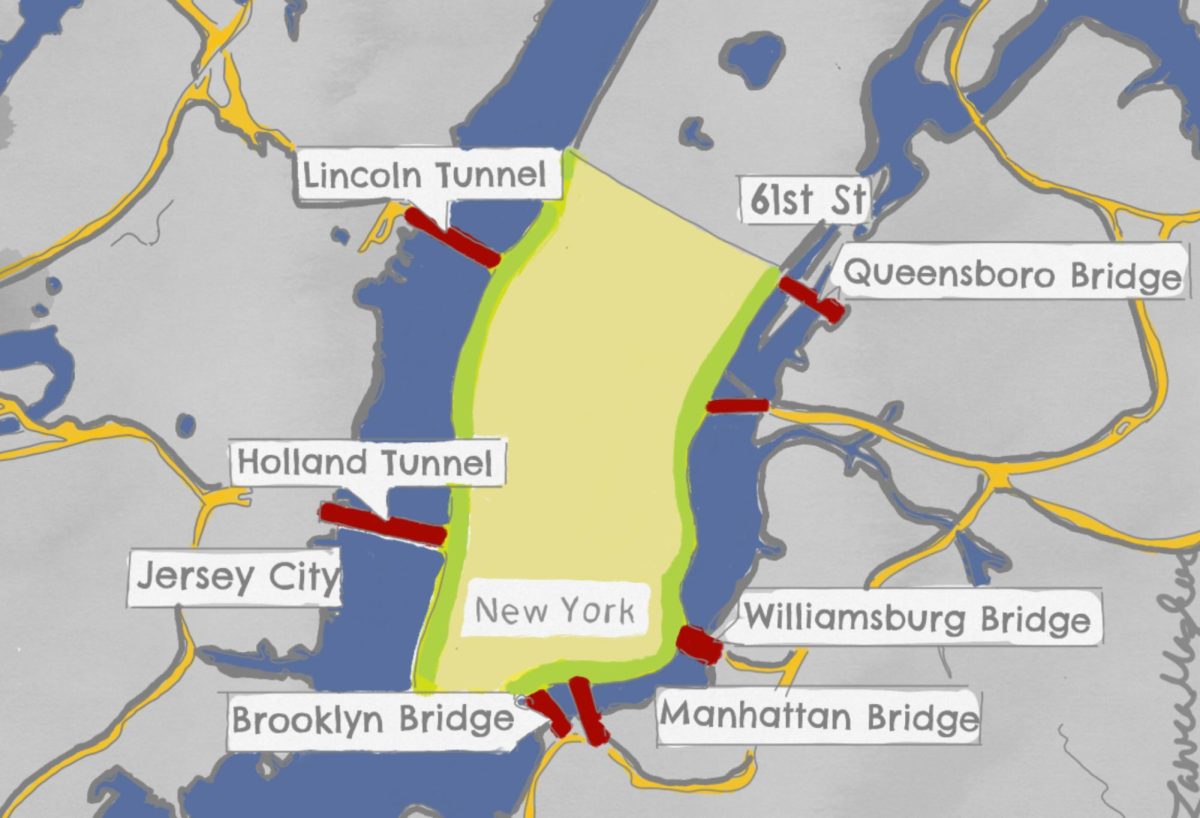

On January 5, 2025, New York City implemented the nation’s first congestion pricing program, introducing tolls for vehicles entering Manhattan’s Central Business District below 60th street. This initiative aims to improve traffic while reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Passenger vehicles are charged a $9 toll during peak hours (5 a.m.-9 p.m. on weekdays and 9 a.m.-9 p.m. on weekends) and $2.25 off during off-peak hours. Small trucks and certain buses incur a $14.40 toll during peak periods and $3.60 overnight, while large trucks and tour buses face a $21.60 toll during peak times and $5.40 overnight. Payments are primarily processed through E-ZPass, with higher rates applied to vehicles billed via Tolls by Mail. The toll is scheduled to increase to $12 in 2028 and $15 in 2031. Specific vehicles, including authorized emergency vehicles, are exempt from the congestion toll. Additionally, discounts are available for certain groups, such as low-income drivers and individuals with disabilities.

In the first week of the new policy, Manhattan traffic dropped by over seven percent. However, the new tolls have prompted concerns among businesses and residents. Companies providing services within the CBD, like food distributors, anticipate significant annual costs due to the tolls, potentially leading to increased prices for consumers. For instance, some food distributors estimate additional expenses of up to $300,000 per year due to increased costs of truck deliveries, which may result in higher food prices citywide.

The congestion pricing program has also sparked political debate. Governor Kathy Hochul has faced criticism for supporting the tolls while opposing other economic measures like tariffs, with opponents labeling her stance as hypocritical. Additionally, some city officials who endorsed the tolls are exempt from paying them due to their use of official vehicles, leading to further public disapproval.

Proponents of congestion pricing, however, have often cited examples of other successful implementations of congestion pricing. Cities like London, Stockholm and Singapore have reduced traffic and improved public transit use through these transit programs. London’s system, introduced in 2003, cut traffic by 15-20% and increased travel speeds, though its effectiveness declined over time due to population growth. Stockholm’s toll, initially unpopular, reduced traffic by 20-25% and later gained 70% public approval after visible improvements in air quality and congestion.

“I think that the toll could possibly be effective in reducing traffic, as it could discourage some drivers from taking that route especially if they have other options,” junior Ava Su said. “I think it depends on how it’s enforced and if people are really willing to pay the increased toll or not.”

While some think the congestion toll will be effective in reducing congestion, many people at NHP are concerned about the outcome.

“While the toll will likely reduce the traffic in Manhattan, it’ll cause backlash since people are already spending so much on gas from commuting and will eat at daily expenses,” junior Isabelle Chan said. “This will also cause public transit users to have to be wary of their suppliers since buses will need to raise prices to account for tolls. There will be better ways, like expanding roads or creating more walkable friendly pathways; tolls will just sacrifice the working class, especially lower class, for the environment.”

“I am not a fan of a congestion toll,” science teacher Mr. Gordon said. “I think it will drive the cost of items in the city up. Increased pricing on delivery could be used to push the cost on to the consumer. I doubt it will be effective in reducing traffic, it might even increase traffic earlier and later on when the toll is not implemented. It almost feels like taxpayers are being punished for going to work or school and just living their lives.”

As of now, NYC’s congestion pricing program remains at risk due to political pressure from President Donald Trump. Trump had instructed New York officials to end the program by March 21, but the city has refused to end the tolls without a court order. Given the uncertain toll that the congestion pricing program will take on the city, many NHP students believe that there may be better ways to reduce congestion.

“I think the city could reduce congestion if they provided some incentive to take public transportation, like a reduced fare,” sophomore Sania Naqvi said. “This could work because getting fewer people to use their cars is ultimately the main goal of this plan. The city could also try to reduce crime on the subway, which is a main deterrent from taking public transportation throughout the city.”

![”[Billie Eilish] truly was made to be a performer and I hope everyone has a chance to see such an amazing show,” junior Nyelle Sarreal said.](https://nhpchariotonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/IMG_1108-e1749239774437-1200x860.jpeg)